In this way, it used the New Testament as a guide to build upon its Old Testament foundation rather than to limit that foundation.

Out of the soil of Utah, it blossomed forth, re-creating itself as parallel to the early Christian church rather than its extension. It was out of this self-image as Israel that Mormonism became a church. The prophecies given to Smith and other early leaders carried forward God’s prophetic interaction with Israel, while the divinely revealed Book of Mormon had important parallels with the Torah God had revealed to Moses. Their Council of Twelve followed Jacob’s 12 sons. In their movement, for example, God restored the ancient Israelite priesthoods of Aaron and Melchizedek. As the religious historian Jan Shipps has shown in her book “Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition,” instead of seeing themselves as ancient Israel through the lens of the New Testament, Mormons understood themselves as the direct re-creation of Israel. The Puritans were Israel, but they were like Israel as the early church - Jesus’ followers - were like Israel.īy contrast, early Mormonism took a different route to Jesus and his message. Although they revered Moses as a leader, he was a leader like Jesus. Matthew’s Gospel and other New Testament writings provided the interpretation through which they understood Moses, ancient Israel and the Old Testament. The Puritans’ symbolism of ancient Israel was shaped by the New Testament’s use of the Old. The main difference between the Puritans and the Mormons lay in their understanding of the early Christian church.

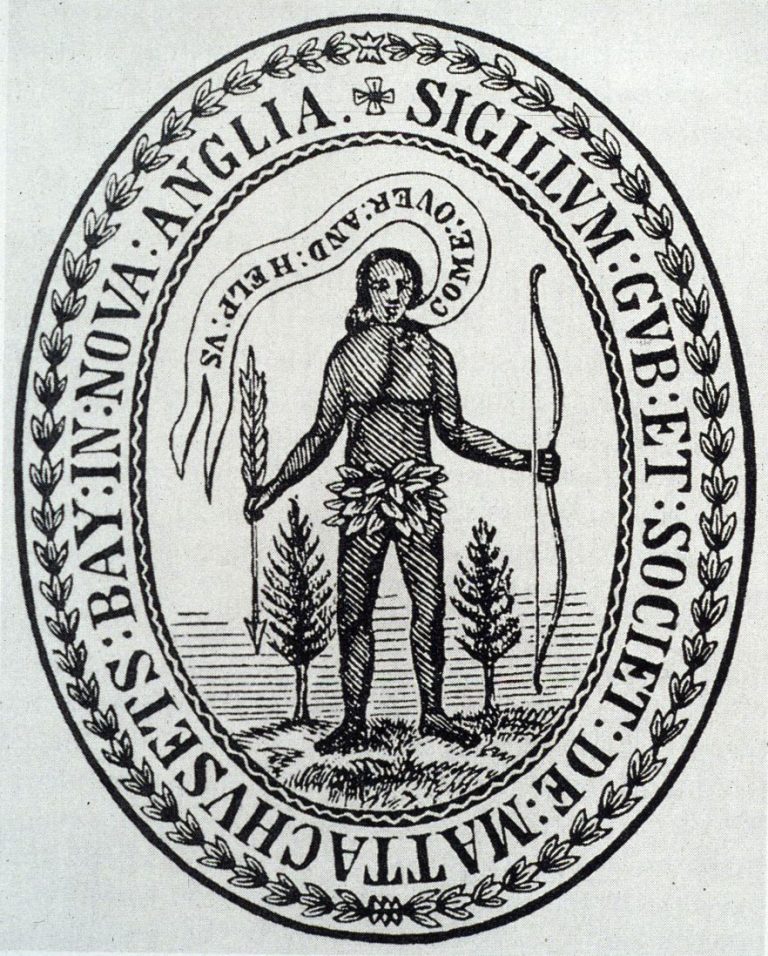

While this difference helped them win converts, it also brought about antagonism and persecution. Their creative use of that model lifted Mormonism beyond mere religious reform, however, and helped to establish The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a new religion, as a new stage in God’s divine plan. In the 1830s and 1840s, Joseph Smith and his followers, likewise, drew upon the Puritan model as they preached their new message. In most cases, the religious movements that survived simply became one more Protestant denomination in the increasing variety of the American religious scene. Although Puritan belief was left behind, the Puritan model provided a means for understanding religious revival and renewal. In the two centuries after the Puritans, many American religious movements envisioned themselves as the new Israelites. The difficulties of the voyage and their life in the New World gained meaning as they drew strength from their belief that they were God’s new Israel. In America, they would build a new Zion, a light shining out to the world to lead it to divine renewal. This parallel was not accidental, the Puritans believed, but came from God’s guiding hand. Just as the Israelites crossed the Red Sea and entered into the wilderness of Sinai, the Puritans sailed the Atlantic Ocean and settled in the American wilderness. If Puritan belief provided an American model for interpreting new religious ideas, then the early Mormons used that model to understand the meaning of their movement.ĭecades of college students have studied Perry Miller’s portrayal of the early Puritans in his book “Errand into the Wilderness.” His key point is that Puritans saw themselves not merely as a Christian reform movement, but as God’s re-creation of the people of Israel, as a “new Israel.” Their flight from persecution in England re-enacted the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt. Since the Mormons were already in the New World, their religious reform became a new religious tradition. One way this statement holds true is with regard to Mormonism’s parallels with the Puritans, the first religious movement of America’s European settlers.Īlthough the Puritans’ goal was religious reform, their exodus to the New World laid the basis for a new nation. The observation that Mormonism is the quintessential American religion has long been a scholarly commonplace.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)